Alpine Plantswoman Amy Schneider

- Martha Keen

- Jan 3, 2019

- 6 min read

What is the appropriate appellation for someone who straddles horticulture and botany? We are delighted to feature Amy Schneider--a woman who gardens on Colorado mountainsides in all weather and elevations, brandishes plant keys with agility and reverence, performs wild collecting of herbarium vouchers, and propagates alpine plants with the seeds from her own expeditions. While Amy considers herself a horticulturist--and her title at Denver Botanic Gardens attests--she relies on her studied grasp of botany to identify the nuances of the alpine wildflowers and grasses she cultivates.

Amy's gratitude for her mentors and colleagues was palpable; correctly keying out rare species and intuiting their preferred communities is a skill that requires years of guidance and shared experience to develop. Her passion for conservation shone through as well, and the products of her recent wild collecting permits will have lasting value to researchers worldwide. In our January Featured Horticulturist edition, we are thrilled to feature Amy's work with alpines, a group of plants that are tiny but fierce, and so nuanced in their adaptations to nature's extremes.

WinH: What is your current position and how did you get there?

A.S.: I am a Horticulturist at Denver Botanic Gardens.

I started working as a summer garden seasonal back in 2008, was hired in 2009, and have worked at the beautiful Denver Botanic Gardens ever since!

At our main site on York Street in Denver, I care for three gardens: our green roof, our iris and daylily collection garden, and our Asian collection garden featuring a steppe area, a collection of woodland plants and cold hardy bamboo.

The fourth garden I take care of is on Mt Evans, about an hour west of Denver. This is in the Mount Evans Wilderness Area, owned by the US Forest Service. Denver Botanic Gardens has had a partnership with the USFS since the 1950s. The Alpine Interpretive Garden is located at an elevation of 11,500 feet and is arranged to feature 6 different alpine plant communities. All of the alpine plants growing in the garden are grown from seed I find on Mt Evans. Every year my work is to find wild species to add to the garden, collect herbarium vouchers for documentation, collect seed and help to propagate the plants, and then take them back to Mt Goliath the next year and plant them in the garden, which surrounds the Dos Chappell Nature Center, a small interpretive alpine museum for visitors.

This year I started an additional wild alpine collection from both the field and from curated alpines at Betty Ford Alpine Garden in Vail for the Global Genome Initiative. The specimens are stored at our Kathryn Kalmbach Herbarium with information about each specimen available through SEINet. The extra leaf sample that accompanies each specimen will be available to researchers for DNA extraction and is stored in our biorepository. Collections are part of the Global Genome Initiative (GGI) and specifically for the GGI-Gardens project, which focuses on plants. The Global Genome Biodiversity Network (GGBN) is how we share our tissue collection with the research community so they know what we have and can request samples.

WinH: What was one of the toughest roadblocks to get to your current position? How

did you overcome it?

A.S.: There are some plant species I have been trying to find for several years with no luck. Typically people try to find a species in the wild by hiking and looking in an area you suspect the plant would occur.

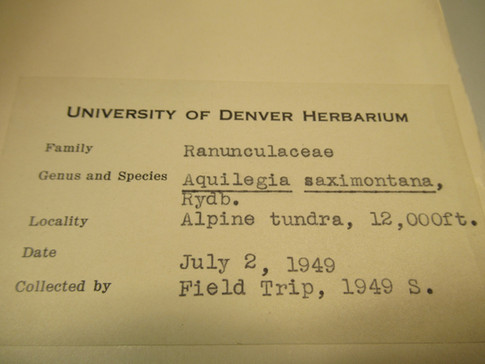

Other times, with more rare species, I have searched through the SEINet and our herbarium for older vouchers. This has been very helpful most times I’ve tried it. Other times it can turn up absolutely zilch. I will find the species folder in the cabinets and get excited and think, cool! Someone found it there in the 1930s! Look at this label! Oh no! It says “Alpine Tundra” for the location information. Another voucher had a label that said “Mt Goliath.” Well, mountains are big. While it’s nice to know that it was collected on Mt Goliath, we need a more specific location. Bad labels with incomplete information are one of the biggest roadblocks.

The other roadblock I face and will undoubtedly continue to face forever is grass and sedge identification. It is proving to be beyond my capacity to see some of these minute described differences. These are things I am attempting to improve through practice, taking notes on my plant keys, and also consulting previously collected herbarium vouchers.

Our former herbarium director, Dr. Jan Wingate, volunteers once a week and when I go to her with my identifications and they are incorrect, she gets me back on track and is always so helpful!!

WinH: With your current work, what do you enjoy most about it?

A.S.: Everything! The beautiful setting and amazing plants, the great staff I get to see every day. Additionally, the independence I have at DBG is probably one of the most treasured parts of my work. Our Director of Horticulture Sarada Krishnan (previously featured in your blog) and my supervisor, Mike Kintgen, our Curator of Alpine Plants, give me their trust and support for alpine collecting projects I am pursuing.

I love all of the hiking, plant scouting and discovery. Spending time in the beautiful Rocky Mountains alone or with co-collectors in the alpine is one of the best things about working here.

Another favorite time is winter, when I have more time to look over my collections from the year, document all of the information, and then plan for the coming season. I enjoy helping to propagate plants for the coming season too!

I also enjoy all the wonderful people I have collected with over the years. I owe many thanks to all my past seasonals and volunteers. Their names are all listed as co-collectors on my herbarium voucher labels.

WinH: What is one of your favorite factoids about a plant or plant group you work

with?

A.S.: I have so many favorite alpine plants with so many cool things about them I love that I don’t know what to answer!

Regarding herbaria collections, I am technically vouchering so I can collect seed as part of my seed collecting permits. Those vouchers become part of our herbarium collection and will be used for other purposes as well. My favorite thing about collecting and preserving specimens is knowing that they will provide information to students, researchers and scientists in whichever endeavor they are pursuing. As it says in my Plant Collection Protocol, a preserved plant specimen is a “lasting and irreplaceable historical record of where and when plants occurred,

attesting to an area’s past and current biodiversity.”

I was delighted when I saw this sticker on many of my collections, showing their usefulness to another person’s research to add to our body of knowledge about alpine ecology.

WinH: Have you been in any tough conditions while working in the field? How did you

manage them?

A.S.: Yes, many times. The alpine is a beautiful environment but can become dangerous very quickly because of the altitude. There is typically a strong wind most of the time, but have many times been caught in sudden storms, thunder and lightning, snow and extremely cold and powerful winds above 12,000 feet. After a few of these experiences, I learned my lesson and come a little more prepared. Head to shelter as soon as possible. A bag of extra dry clothes, jacket and shoes to change into and stay warm helps. There is no drinking water so you must bring your own and you should bring plenty. Dehydration is a problem at high elevations.

It is nice to go with a small group of people so you are not lonely and everyone is a lot safer if anything happens. I have also decided to co-collect more often with fun people who can really hike and climb, who bring a large backpack filled with good snacks, and most importantly are into going to get ice cream before driving all the way back home at the end of the day. I’m looking at you, Nick, Claire and Colin of Betty Ford Alpine Gardens.

WinH: What characteristics does a woman in the green industry need to excel at and be included in field work?

A.S.: Field work just requires common sense, patience and flexibility. Remember it takes a long time to learn about an area you are collecting in and what lives there. I was amazed last summer at an intern who seemed frustrated because she didn’t know any of the plants. Well, that’s because she hadn’t ever worked in the alpine before. You can’t expect to know everything at once. I’m still learning and finding species after all these years. It may take many attempts to finally find a species and you may even be the first to document the occurrence. That’s exciting!

Remember there will be other people in the future who will look at your collection and try to go find the same species perhaps 50 years later, so it’s important to fill out locations and your name.

If you are a woman field collector, I just want to say I support you, from Amy in Colorado!

Image caption: Androsace chamaejasmae, Castilleja rhexifolia, and Paronychia pulvinata

All photos copyright Amy Schneider except where otherwise noted.

Comments